Many moons ago I was a Second Officer on Boeing 747-400’s for a large Hong Kong based international airline, which I remember fondly. This story revolves around a flight from Hong Kong to Melbourne about a year after I had checked out, late 1993. This was a three crew operation, Captain, First Officer and myself. The Captain on this flight was asked this question about whether we were ready to go; He answered in the affirmative – and probably shouldn’t have. I can only speculate to this of course – because I wasn’t on the flight deck at the time … or the aeroplane.

From my Practices and Techniques document – there are two very loaded questions a Captain or Pilot Flying can be asked. The second of these is “Are you ready for the Approach?” and is more applicable to the simulator.

But the first is this question from the Purser/Flight Manager “Are you ready to close doors, Captain?” and is a loaded question indeed. Essentially it sums up the entire (often out of) sequence of frenetic activity that can occur before you push and start the aircraft. Get this question wrong and you may have to open the door again – which seems straight forward, but that means having someone there to open it; an aerobridge connection or stairs to step out onto, and ground personnel there to assist – all of which may well have headed off to their next aircraft. It also means ensuring the door is dis-armed (evacuation slides) before the door is opened …

As a new Captain I identified this issue early on in my line training (the hard way) and made myself a little clipboard checklist. Over time of course I used this less and less. But every now and then (particularly since coming to my latest airline) when the sh!te has hit the fan and pre-flight has been a Shiva-esque display of multiple hands going everywhere dealing with everything – when confronted with the Flight Manager (no, that’s not me) wanting to close doors – my first reaction is “No!” (internally)?and I flip over my clipboard to see what we’ve missed. The answer is often illuminating.

Do you notice what’s missing from this list? It’s “All Crew On Board.“

Refuelling Problem

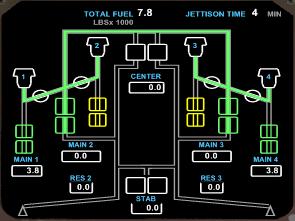

On all flights, at some point the refueller (after being given the final fuel load, based on the anticipated final weight of the aircraft) calls up from the nose of the aircraft via headset/intercom to confirm that the flight crew are satisfied with the fuel load, and the fuel bowser/truck can be disconnected. This check by the flight crew consists of reviewing the total fuel on board, as well as the distribution across the various tanks, against the fuel required figure from the flight plan. Having received clearance to disconnect – the refueller does so, then comes up to the flight deck and starts the paperwork. No job is over until …

On all flights, at some point the refueller (after being given the final fuel load, based on the anticipated final weight of the aircraft) calls up from the nose of the aircraft via headset/intercom to confirm that the flight crew are satisfied with the fuel load, and the fuel bowser/truck can be disconnected. This check by the flight crew consists of reviewing the total fuel on board, as well as the distribution across the various tanks, against the fuel required figure from the flight plan. Having received clearance to disconnect – the refueller does so, then comes up to the flight deck and starts the paperwork. No job is over until …

On this particular departure the refueller rang but when we looked at the EICAS to determine fuel on board – it was blank. Further examination revealed that the inner right wing tank was not showing a fuel quantity. With a tank indication missing – the total fuel on board could not be determined by the FQIS (Fuel Quantity Indication System). The Captain asked the refueller to come to the flight deck.

Meanwhile we examined the MEL (Minimum Equipment List) to determine if dispatch was possible – or were we looking at a delay while Engineering fixed the system? As it turned out – we could go, but first were required (unsurprisingly) to accurately determine the actual fuel on board. The Captain, Refueller and Engineer discussed it – and the Refueller and Engineer went off to “Dip” the tank. I must have looked intrigued at this point because the Captain asked me if I’d seen this done before – I had not – and instructed me to go with the Engineer to observe, and bring the paperwork back when I came up. Pleased with the Captain’s interest in my professional development – I headed off with the Engineer.

I must explain at this point that this was Hong Kong’s Kai Tak airport – before the days of the mega-airport that is the current Hong Kong. It was also late evening and nearing the time of peak departures with flights queueing up to depart to Europe. Those who have experienced that time and place will remember it clearly – it was a small, congested apron with spaces for just a few aircraft at the terminal and far many more aircraft parked “remote” requiring busses and stairs to get passengers up to the doors. There were ground vehicles of all descriptions going in all directions, with flashing amber lights projecting the importance of their particular task. Literally hundreds of such vehicles, across the (small) expanse of the apron areas of Kai Tak. It was a magical place for a young pilot who yesterday stepped out of a Cheyenne, today into a 747.

I must explain at this point that this was Hong Kong’s Kai Tak airport – before the days of the mega-airport that is the current Hong Kong. It was also late evening and nearing the time of peak departures with flights queueing up to depart to Europe. Those who have experienced that time and place will remember it clearly – it was a small, congested apron with spaces for just a few aircraft at the terminal and far many more aircraft parked “remote” requiring busses and stairs to get passengers up to the doors. There were ground vehicles of all descriptions going in all directions, with flashing amber lights projecting the importance of their particular task. Literally hundreds of such vehicles, across the (small) expanse of the apron areas of Kai Tak. It was a magical place for a young pilot who yesterday stepped out of a Cheyenne, today into a 747.

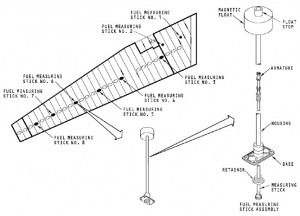

Since we were remote it was down the stairs to the outside of the aircraft. The Engineer explained to me that we didn’t have to actually “dip” the tanks (much to my disappointment) – there were small devices built into the underside of each wing. These projected upwards into the fuel tank. You unscrewed them and pulled them down and a measurement strip along the side gave you a number to look up on a chart and determine the quantity of the tank. Quite elegant, I thought.

Of course the practicalities of this meant a high lifter to get to the underside of the wing. The Engineer positioned the high lifter and up we went. He unscrewed the “dip stick” took a measurement, and wrote down a figure. As I looked around I could see there were measuring sticks everywhere, all numbered. I asked why there were so many, given there were only two tanks in the wing? ?The answer was that depending on how much fuel was in the tank – you used a different stick. Ha, I thought – “How do you know you have the right one?” I asked. He showed me on a chart that you start with the anticipated fuel quantity in the tank (nearly full in this case) and that took you to a particular stick. So since we believed we had XX.X tons in this tank, so we should be at stick number … not this one. Oops.

Of course the practicalities of this meant a high lifter to get to the underside of the wing. The Engineer positioned the high lifter and up we went. He unscrewed the “dip stick” took a measurement, and wrote down a figure. As I looked around I could see there were measuring sticks everywhere, all numbered. I asked why there were so many, given there were only two tanks in the wing? ?The answer was that depending on how much fuel was in the tank – you used a different stick. Ha, I thought – “How do you know you have the right one?” I asked. He showed me on a chart that you start with the anticipated fuel quantity in the tank (nearly full in this case) and that took you to a particular stick. So since we believed we had XX.X tons in this tank, so we should be at stick number … not this one. Oops.

So down again in the highlifter, a bit of a re-position and up we go again. Measurements taken in silence this time without the meddling influence of the junior pilot (so junior he’s clearly not even required on the flight deck at this point) – and we’re done. High lifter down and driven away, paperwork completed and handed over, and I’m headed back to the stairs to the L2 Door.

Or at least that was the plan. I step away from the refueller/engineer to find … the door is shut; the stairs are gone; Engine #4 has been started in concert with another Engineer talking to the flight deck from the nosewheel. Oops I’ve been left behind.

What has to happen next is clear to me. Engine #4 must be shut down. ATC will need to be advised, with possibly a new start/push/airways clearance sought. Stairs must be found and brought to the aircraft. The door opened and the errant Second Officer re-admitted to the aircraft (if not the flight deck …). The process has to be reversed to regain a departure once more. All this will mean a significant delay in an airline that is very OTP (On Time Performance) conscious. All because of a junior crew member who seems to have forgotten that his place on the aircraft when it’s leaving is on the inside ..

I manfully resist the urge to hitch a lift back to the terminal and go home – or just head for the nearest fence and jump it (after all, if I was really required for this flight, wouldn’t they have waited for me?) – and head over to the Engineer on headseat at the nosewheel. He looks at me in surprise and hands me the headset (Chicken!) and I advise the Captain of my predicament.

Me : “Skipper – it’s Ken.”

Captain : ” Ken? Ken who?”

Me : “Um, Ken the Second Officer.”

Captain : “Oh, of course. Where are you?”

Me : “At the nosewheel. I have the refuelling paperwork for you, if you still want it.”

Captain : “What? Good Lord! OK, standby …”

It was perhaps 20 minutes to get stairs after the engine was shut down and secured. Once in place I headed up the stairs, past the some quizzical cabin crew and disinterested upper deck business class passengers, and I tail-between-my-leg’d my way into the flight deck. Paperwork handed over and I sat at the very very back (or tried to) and stayed as quiet as possible.

With the doors closed (again) and the stairs removed (again) and clearance from Tower and Nosewheel Engineer (again) – Captain starts Engine #4. Or tries to. Whether it’s a second start issue or a judgement from the Aviation Gods – it won’t start. The start valve (which releases air from the APU to the motor used to turn the engine for start) won’t open. This means a manual override engine start, and a further delay while engineering get that process into action. Eventually we get all four engines started and we commence taxi.

With the doors closed (again) and the stairs removed (again) and clearance from Tower and Nosewheel Engineer (again) – Captain starts Engine #4. Or tries to. Whether it’s a second start issue or a judgement from the Aviation Gods – it won’t start. The start valve (which releases air from the APU to the motor used to turn the engine for start) won’t open. This means a manual override engine start, and a further delay while engineering get that process into action. Eventually we get all four engines started and we commence taxi.

My role on this flight deck now is clear. I remain diligent in my monitoring and paperwork roles, and above all, quiet. No-one says anything about what happened at departure until well after top of climb, at which point the First Officer draws out the aircraft log book and says with deliberate … deliberance “What do you want to put the delay down to, Captain?”

Skipper leans his seat back at this point and asks of the flight deck (and the universe in general) – “Hmmm. What was the LAST thing to go wrong on that departure …?”

First Officer says “Well, that would be the start valve on Engine #4?”

Captain adjudicates “Right – delay is clearly down to Engineering then.”

No further comment was passed on my absence, or of anyone’s role in our departure adventures, and we sailed on through the night across the China Sea towards Australia.

Upon reflection, maybe I need to update my checklist …