Weather avoidance is part and parcel of an airline pilot’s standard task list. From the Mark One Eyeball to the Rockwell Collins WXR-2100 Weather Radar there are various tools available to assist in this task; all of which leverage the training and experience an airline pilot brings to the flight deck. But my last trip illustrates the changes we’ve seen over the past few years in weather avoidance becoming a wider task that just the pilots on the flight deck, so I thought I’d share it here.

On a recent trip Sydney to Los Angeles I returned from crew rest towards the middle of the flight (halfway between Fiji and Honolulu) to be advised by the outgoing crew that we’d received the following message over ACARS (basically a text message via satellite) warning of some weather enroute. This came to us through our CPDLC (Controller to Pilot Datalink Connection), part of the FANS initiative (Future Air Navigation System) that was so new not that many years ago, but is now nom de guerre in today’s flight decks. How’s that for a series of aviation acronyms?

On a recent trip Sydney to Los Angeles I returned from crew rest towards the middle of the flight (halfway between Fiji and Honolulu) to be advised by the outgoing crew that we’d received the following message over ACARS (basically a text message via satellite) warning of some weather enroute. This came to us through our CPDLC (Controller to Pilot Datalink Connection), part of the FANS initiative (Future Air Navigation System) that was so new not that many years ago, but is now nom de guerre in today’s flight decks. How’s that for a series of aviation acronyms?

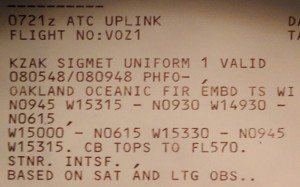

To translate:

At 0721 UTC time, this message is from ATC (UPLINK) to flight VOZ #1. KZAK (San Francisco Oceanic Control) advising us that a significant meteorological advice (SIGMET) has been raised since our departure, based on satellite (SAT) and lightning (LTG) observation (OBS). This weather warning refers to Cumulonimbus cloud (CB) which typically means thunderstorms (TS) with associated turbulence, lightning and rain in this part of world (near the Equator, over the Pacific Ocean). Latitude/Longitude waypoints are given that describe an area in which the weather was observed to be. The weather is stationary (STNR) and intensifying (INTSF), and the tops of the CB clouds are up to 57,000 ft (well about our cruising altitude).

This flight was a check-to-line for a new pilot joining the 777 fleet, a relatively junior cruise pilot who has completed the course of simulator and aircraft training and is now under evaluation to be released to line operations as a fully fledged Second Officer. So far the check was going well, and the candidate had demonstrated better than acceptable knowledge and good airmanship throughout the flight to this point. Time for a teachable moment …

I asked how we could check our route proximity to this observed weather given that it was nearly a thousand miles in front of us, intensifying and probably in our path given that ATC had sent it to us directly. My trainee’s answer was the route plotting chart, and when we got it out we found the previous crew had thoughtfully already plotted it for us. It showed our approximate route cutting through the corner of the proscribed area. Time to push for some FMC knowledge.

I asked how we could program the co-ordinates into the Flight Management Computer (FMC) to display the area on our Navigation Display (ND). Eventually (we) worked out there were three ways.

Firstly the four waypoints could be created as Fix Page entries (which display as green circles) and we could draw lines out of them between the waypoints. I’ve played with this in the past, but it’s a pretty cumbersome solution, requiring you to work out bearings between these points, the lines of which continue out into space until you have this Salvador Dali like drawing on your ND.

Another solution is to enter the waypoint concerned into the LEGS page of the FMC. While typically modification of the active flight plan is verbotten unless it’s in accordance with an ATC clearance, you can insert additional waypoints into the FMC after the end of the active flight plan. These waypoints don’t affect time/fuel predictions because they are after the route destination (KLAX) and the FMC doesn’t consider them relevant to these calculations. It’s a good idea before you confirm-execute this (as is required of all modifications to the active route) that you check fuel predictions aren’t affected. This route modification shows on both pilot’s NDs and provides a very clear picture about an area of concern, whether it be weather, volcanic ash, or something else.

Another solution is to enter the waypoint concerned into the LEGS page of the FMC. While typically modification of the active flight plan is verbotten unless it’s in accordance with an ATC clearance, you can insert additional waypoints into the FMC after the end of the active flight plan. These waypoints don’t affect time/fuel predictions because they are after the route destination (KLAX) and the FMC doesn’t consider them relevant to these calculations. It’s a good idea before you confirm-execute this (as is required of all modifications to the active route) that you check fuel predictions aren’t affected. This route modification shows on both pilot’s NDs and provides a very clear picture about an area of concern, whether it be weather, volcanic ash, or something else.

They aren’t uplinked to ATC unless you fly over KLAX at the end of the flight with the waypoints still there, but they display on the ND quite clearly. To provided additional demarcation you can insert a route discontinuity into the LEGS page to highlight the point at which our plan ends and our playing around begins.

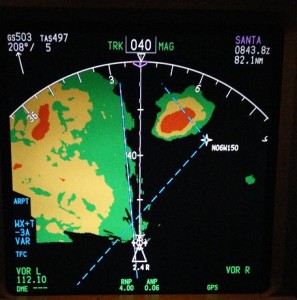

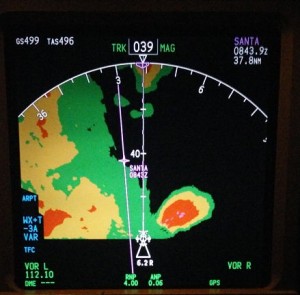

The display on the ND is quite clear and as you can see not only a good awareness tool, but in this instance, indicated that ATC were pretty accurate in their provision of information. It’s a little hard to tell from this image – but the scale of distance from the aircraft (triangle at the bottom) to the top of the ND is 640 nm (about 1200 km) with our encounter with the weather due at about 300 nm. Weather radar only begins to pick up weather at 320 nm and doesn’t really paint it clearly until much closer in. Still time for some more training before the dodging begins …

The display on the ND is quite clear and as you can see not only a good awareness tool, but in this instance, indicated that ATC were pretty accurate in their provision of information. It’s a little hard to tell from this image – but the scale of distance from the aircraft (triangle at the bottom) to the top of the ND is 640 nm (about 1200 km) with our encounter with the weather due at about 300 nm. Weather radar only begins to pick up weather at 320 nm and doesn’t really paint it clearly until much closer in. Still time for some more training before the dodging begins …

The inherent risks of this technique include accidentally leaving the waypoints there long after you’ve flown past; or after you’ve left the flight deck and the relief crew have taken over (low-ish); and potentially some visual confusion between the active route you’re following and the display of the active route that comes from well after your flight plan. The aircraft won’t confuse the two and fly the wrong path, but when you’re manually navigating your way around storms it would be possible to get confused between which magenta line you want to be following …

Some instructors/pilots do not like this technique because of these potential risks. There’s really no genuine need to do this in any case, it’s as much an exercise in increasing FMC awareness when you have a plotting chart to work with – but it’s a useful tool in the toolbox in any case. I’m ambivalent about it, but that’s probably because I have yet to stuff up when using it (no doubt my time is coming …).

So my young Padawan (no I did NOT say that) is there another way?

The other method involves using the inactive route feature of the FMC. Our FMC has the ability to store two complete routes. By convention we cruise along in “Route 1” (active), and as such “Route 2” (inactive) can be used for contingency planing (diversions, terrain escape routes, etc). But most often it remains unused, and when we arrive at destination it holds a complete copy of the route flown, copied during the pre-flight and not referred to again.

We built the four waypoints using the provided Latitudes and Longitudes into the FMC, and looked at the ND. Because Route is not the active route, the header (“RTE 2 LEGS”) on the FMC is in Cyan (blue) and the route displays in blue on the ND. Additionally the display on the ND is only on the side of the aircraft on which the FMC is being used to show active route. So if I’m looking at the inactive route on the FMC, I see the inactive route on the ND – but the other pilot will not. This is certainly an acceptable, workable compromise.

We built the four waypoints using the provided Latitudes and Longitudes into the FMC, and looked at the ND. Because Route is not the active route, the header (“RTE 2 LEGS”) on the FMC is in Cyan (blue) and the route displays in blue on the ND. Additionally the display on the ND is only on the side of the aircraft on which the FMC is being used to show active route. So if I’m looking at the inactive route on the FMC, I see the inactive route on the ND – but the other pilot will not. This is certainly an acceptable, workable compromise.

Our efforts were quite successful and as we drew closer to the weather and the weather radar was able to paint the cells more clearly, it became apparent what ATC had seen on satelite imagery. By the time we got there it was definitely INTSF but not so much STNR as it was moving south across our track.

We ended up deviating initially right and then left of track to avoid the weather, encountering only light turbulence which marks this as a successful weather encounter in my book. The following series of images give you an idea of how we do our job. Note that during some of the shots below I was playing with the variable gain on the weather radar (VAR) which tends to over-highlight, but can fill in some of the areas between weather.